31 August 2012

30 August 2012

The face

His was a hard face to miss, for reasons I didn't understand. You know how you notice someone -- in a bus, on a corner, standing in line -- and you can't figure out why? It was like that.

He wasn't particularly distinctive. Handsome in a bland way, like a second-tier actor in 1950s movies. A clean, square jaw, well-proportioned features. Brown eyes, fair hair, short nose. He'd play the up-and-coming lawyer or junior executive, Rock Hudson's buddy, say, and get the spunky ingenue in the end.

He wore pair of glasses with frames like mine, square and black. I wondered if he looked a bit like me, or like a relative of mine, and maybe that was why I'd pick him out in the line of trumpet players in the jazz band or among the baritones in the choir.

The woman he raped wrote a memoir about it, about her process of survival. This was a topic more congenial to the newspaper's editors, who published a front page story about her healing and recovery and so on.

He wasn't particularly distinctive. Handsome in a bland way, like a second-tier actor in 1950s movies. A clean, square jaw, well-proportioned features. Brown eyes, fair hair, short nose. He'd play the up-and-coming lawyer or junior executive, Rock Hudson's buddy, say, and get the spunky ingenue in the end.

He wore pair of glasses with frames like mine, square and black. I wondered if he looked a bit like me, or like a relative of mine, and maybe that was why I'd pick him out in the line of trumpet players in the jazz band or among the baritones in the choir.

Because he was a star at his high school. He played jazz trumpet well, and went to all-state jazz band, too. He played solos, smoothly. He sang in a pleasant, old-school baritone, so beautifully that he took the lead in musicals and performed solos during choir concerts. He even had a featured act in once, crooning All of Me, à la Sinatra. He was smart enough to invite a cute girl in to the act and make it a duet.

Besides acting and singing and blowing the trumpet, he made short films. He earned top grades. He was accepted to NYU. I wished him well, from a distance, relieved that I wouldn't be puzzling over why my eye was drawn to him.

Then I heard a rumor: He raped a girl at a graduation party. I didn't believe it. I don't believe many rumors, particularly those spread by teenagers. He didn't seem the type, either. He had girlfriends. Wasn't a kid who'd sequester himself in front of RedTube or World of Warcraft.

And, two kids, drunk: maybe he was a jerk, and pushed things too hard, but it probably stopped well short of rape. Maybe she decided she didn't like sex with him. Maybe someone hated him and wanted to trash his reputation out of jealousy.

Other rumors surfaced about other rapes.

Then he confessed to that rape at the party. He received a light sentence: three years, probably as part of a plea deal. The details were murky, because he hadn't reached his eighteenth birthday. The local paper, usually eager to spread around a bit of muck, was quiet on this one. The plea spoke of familial money, discretion, skilled lawyers and a compliant DA. They couldn't blot out the crime, but they did what they could.

If, God forbid, it had been my daughter . . . well, let's not talk about it. I don't want to think about it or imagine it. Just two points. First, I believe in retribution more than I believe in justice. Justice is fine for people I don't love. Retribution would only be the beginning for someone I care about.

Second, say what you will about the old-fashioned patriarchy, but one point gets missed. In the old days, and today, among my blue collar relatives, if you mess with our sisters, wives or daughters, you would get hurt. Chivalry didn't mean just opening a door in time. It meant protection. When protection failed, it meant retribution. The men would assemble and take care of business. It still happens. You beat our sister, our daughter, our cousin, you receive a beating in return.

This does not address the central problem of violence against women. But, in some cases, it might make a lesser psychopath pause. If my man here had known he would risk injury and death of his own, maybe he might not have gone through with it. He might have paused.

As it is, he's losing a chunk of his upper-middle class dream, which is pathetic, but not, by my lights, nearly enough.

I wish her well. I hope she continues to recover. My cousin, who was raped by a stranger who broke into her apartment late one night, still hasn't gotten over it. Some women tougher, resilient, manage.

If you read between or through the lines of the article, you realize just how brutal the rape was. A rotated hip joint. Other injuries are alluded to, but glossed over in favor of the healing slant of the story. But enough is there that I can say, without melodrama or without exaggerating, that the guy, that suave baritone and fine musician, was also an evil motherfucker.

And the only clue I had was that vague disquiet when my eye was drawn to him rather than the other kids on the stage.

2

Back when serial killers were in vogue, a book came out called The Killer Beside Me. A woman who'd known Ted Bundy for years wrote about her experiences with him as well as what she later learned about his gruesome career. She knew him as a co-worker and friend. He was handsome, witty, a great guy.

Who just happened to butcher young women for fun.

Who just happened to butcher young women for fun.

We tend to ridicule the chumps on the TV news who babble on about what a regular guy he was while in the background, backhoes dig up corpses. We'd know, we think. How could you not know?

The mug shot and the pictures that will run of the monster in his prison jumpsuit will further confirm our self-regard. That guy? Total killer. We ignore that nearly everyone looks like a murderous freak or pervert in their own official pictures. Check out your own driver's license, and tell me: what conclusions would someone draw if they saw that on the evening news?

The mug shot and the pictures that will run of the monster in his prison jumpsuit will further confirm our self-regard. That guy? Total killer. We ignore that nearly everyone looks like a murderous freak or pervert in their own official pictures. Check out your own driver's license, and tell me: what conclusions would someone draw if they saw that on the evening news?

Villains don't come equipped with handlebar mustaches that they twirl or flat 100-yard stares and gnarly tattoos. Of course, we know that. But we also forget or don't quite realize that they come with no tell-tale signs at all. Perhaps, at most, we might experience a certain disquiet, a whisper of worry.

And, even though we hate to admit it, we expect evil to be glamorous. No matter what we may have learned as adults about the "banality of evil," hundreds of tales and movies and myths have either reinforced or trained us to believe that some terrible beauty surrounds evil, some incredible magnetism.

Maybe we believe that to excuse ourselves when we fall short of our own better impulses.

So I learned a lesson, one that's hardly a secret.

To pay more attention to the disquiet that intrudes.

To recognize that this disquiet could come from that Bosnian next door who sees his chance and kicks you out the house your family lived in for a few generations. Or the Hutu who picks up his machete.

Or the high school kid with a great future ahead of him.

Or, finally, the one in the mirror.

Maybe we believe that to excuse ourselves when we fall short of our own better impulses.

So I learned a lesson, one that's hardly a secret.

To pay more attention to the disquiet that intrudes.

To recognize that this disquiet could come from that Bosnian next door who sees his chance and kicks you out the house your family lived in for a few generations. Or the Hutu who picks up his machete.

Or the high school kid with a great future ahead of him.

Or, finally, the one in the mirror.

Vintage misogyny

Though some feminists regard “rape equals devastation” as sacred fact, the notion that a man can ruin me with his penis strikes me as the most complete expression of vintage misogyny available. Common sense instructs us that it is far more “dangerous” to insist to young women that they will be broken by an unwanted sex act than it is to propose they might have a happy, healthy, and sexually pleasant future ahead of them in spite of a sexual assault.from Live Through This, by Charlotte Shane

via The New Inquiry

27 August 2012

"I realised I was going to die. . . "

I realised I was going to die and when that gets into your mind that’s a motherfucker. It utterly changed me for a while there. I thought, ‘I’m not going to sit here and wait for things to happen, I’m going to make them happen, and if people think I’m an idiot I don’t care.’

— Wayne Coyne, Flaming Lips frontman, on the time his Long John Silver’s was held up when he was 16

When everything is recorded, nothing is remembered

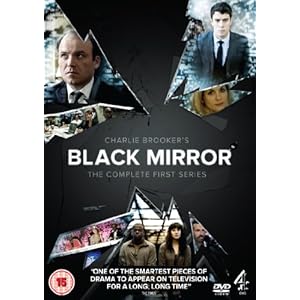

"2. An interesting take on this is the British series Black Mirror, three separate stories of "our unease with the modern world." Spoilers coming: In the second story, the youth are put on stationary bikes to create energy for the world, and are paid in, essentially, Facebook credits that serve also as money. The only way out of this enslavement is to get on Hot Spot-- i.e. to become famous. One young black man rises up against the system with the only violence he has available: he goes on Hot Spot and threatens to stab himself in the neck with a shard of glass unless he's allowed to rage against the machine. But rather than gas the theatre or send in the snipers-- they give him his own weekly talk show where he is safely allowed to rage against the system, in between commercials.

"However, the true import of that episode is only revealed when considered with the first episode, in which the Princess (e.g. of Wales) is kidnapped, with a single ransom demand: the Prime Minister must have sex with a pig, on live TV. Is the Princess's life wirth it? Should they negotiate with terrorists? But all of this is cover for the real conflict: if he does it, he'll be disgraced, most certainly not re-elected.

"He does it: it takes over an hour, some tranquilizers and some Viagra. It is moving, because as he cries through the sex act, all of England is watching from pubs, cheering and jeering. However, the final post-credits scene reveals the secondary consequence of the always-on, broadcast world: after a year, the Prime Minister is happily re-elected. No one even remembers the pig incident.

Together, the two episodes suggest that not only does appearing on TV trivialize events, but it temporizes them. When everything is recorded, nothing is remembered."

via the Last Psychiatrist

26 August 2012

22 August 2012

Le Samourai: Melville's work of art

Le Samouraï: Jean-Pierre Melville's Work of Art from Edwin Adrian Nieves on Vimeo.

"...what I have to say is very simple and very short: He's the greatest director I've had the good fortune, pleasure and honor to work with up to this point. It'd take too long to explain. He's wonderful. He knows more about cinema than anyone. He's the greatest director I know, the greatest cameraman, the best at framing and lighting, the best at everything. He's a living encyclopedia of cinema."

- Alain Delon on Jean-Pierre Melville

17 August 2012

Sokurov on power

Why make three movies on historical subjects and one on a fictional one? "Why do you think?" I suggest Faust is a sort of prequel to the other three. "Maybe," he nods. Or is it that the first three deal with the death of power, whereas Faust addresses its acquisition? "But he never gets this power," Sokurov says. "It's impossible to have this power, because it doesn't really exist. It only exists to the extent to which people are ready to submit to it. Power is not material." Do some people have no choice but to submit to power? "No. There is always choice. Even during Stalin's terror, people had choices. They could betray or not betray, for example." Does he mean that people were persuaded, rather than forced, to submit to power?

"I would be more precise, even," he replies. "They wanted it. Because it's the most comfortable position for most people. We enjoy being forced. It takes responsibility off your shoulders. People are more afraid of responsibility than anything else. Especially all-encompassing responsibility for your country, for the security of your people, for war and peace. Many millions survived only because they withdrew from these responsibilities. For example, they voted for Hitler, they tolerated Stalin. Millions of people did nothing to stop the Cultural Revolution in China. Just like now most of us are refusing to think about the conflict going on between Christian and Muslim civilisations."

14 August 2012

09 August 2012

The Woodmans

Francesca Woodman made visionary photographs. She created a

body of work that her peers and parents recognized for their specific genius,

and that have since gained worldwide renown, been collected by major museums,

ripped off by fashion photographers and form the basis for a cult. She’s big on

Twitter. Much in the same way young female poets have to contend with Sylvia

Plath, young female artists wrestle with Francesca Woodman’s visions.

She achieved this before she committed suicide at 22 by

jumping off a tall building in New York. The suicide, like it or not, adds the

glamour of death to her story, as it does for Ian Curtis, Adrienne Rich or

Vincent Van Gogh.

The Woodmans is a documentary about her family. Her father,

mother and brother are all artists themselves. None of them, as they themselves

note ruefully, have reached anything like the acclaim of Francesca. They’re

collected; they’re in the Whitney and so on, but: not that famous.

Betty, a Russian Jew from Boston married George from New

Hampshire and Harvard. George’s family, classically WASP, refused to have

anything to do with him after the marriage. They moved west, got jobs at the

university in Boulder and had children, first Charlie, now a video artist, and

then Francesca. “Gift/calamities,” as George calls them.

Betty and George – “so very married” as Francesca would

write in her diaries – share a fierce commitment not only to art, but to living

life esthetically. They eat from the dishes Betty, a ceramicist makes. Their

house in Boulder is a modernist art installation as much as a home.

"Our children learned that art is a very high priority;

you don’t mess around. They learned this is a very serious business at an early

age, " Betty says. The couple buys a farm in the hills outside of

Florence. They send the children to the Uffizi with notebooks so the parents

can work undisturbed.

Betty’s ceramics are functional, cheery, decorative.

George’s paintings are abstract, cool, about pattern and repetition.

At 13, Francesca receives a medium-format camera as a gift

from her father. She starts taking photos and never really stops until the end

of her life. They’re mostly self portraits, mostly nude, dreamlike, gritty,

mysterious, personal, Dionysian, even. "My art is about myself, for a lot

of wrong reasons," wrote Francesca Woodman in her journal.

Yet they recognized the brilliance of her photographs

immediately.“She was so good; she made my own work look kind of stupid,”

George Woodman says. “I wouldn’t mind getting a bigger slice of that cake myself.”

After boarding school at Phillips Andover, Francesca arrived

at the Rhode Island School of Design a fully-fledged artist with a distinct

vision. She worked hard. Her fellow students were awed and impressed. She was

“intense,” “dramatic,” a “rock star.” Some loved her.

Next, she went to New York. Her parents had also recently moved

there wanting to jump start their careers.

Francesca struggled, couldn’t find work, didn’t get a major

gallery show, ended up assisting a fashion photographer. A breakup with her

boyfriend triggered depression. Suicide attempts followed. Her parents “babysat”

her, and found her a therapist who in turn prescribed medication. She seemed to

do better. Then, late January, she threw herself from the top of a building.

The story turns back to the family and friends. The friends

choke up when they speak of Francesca’s suicide. George and Betty know what the

filmmaker’s up to, respectful as he is and as the documentary is. They do not

shed tears. Betty’s eyes harden. It’s a subject she won’t deal with. Period.

George, haunted, won’t say much either. Old school. Or, wary survivors.

After their daughter’s death, Betty stops working. Then she

turns away from functional to fine art ceramics. George reacted differently to her death, as Betty

notes with a hint of a mother’s jealousy of a daughter’s place. He couldn’t

focus, then turned to Emily Dickinson’s poems.

The film shows George at work. He’s taking photographs now

with a medium-format camera of young women who are frequently nude. The model

in the film is reminiscent of his daughter. The photos themselves are layered,

lush and sensuous.

As the film draws to a close, we see Charley arrive at the

Tuscan farm with his wife and child. Betty’s commission at the U.S. Embassy in

Beijing goes up, an exuberant mish mash of color. We see the surviving Woodmans in the lobby,

robust in old age, he a hale country doctor from New England, she, an indestructible

babushka in striped socks and sandals.

The documentary, directed by Scott Willis, is lucid and

respectful. It’s an authorized version. He had access to Francesca’s diaries.

Her words float up out of the notebooks. He features her photographs

throughout. She made some videos as well, and he uses these to great effect, the

soft-edged black-and-white VHS dusty and ghostly. We hear her voice,

surprisingly girlish.

It’s a tasteful film, made up of well composed shots and

close ups, mostly of George and Betty, and it remains their story, finally.

It’s brisk, too, clocking in at 82 minutes. Formally, it’s straightforward –

talking heads, the subjects working, the subjects at home, archival material,

well crafted. It pulls back at key moments and lets you draw your own

conclusions, or makes you fill in the blanks.

It leaves several unanswered questions. The main one is: Why

did she do it? The suicide itself, as central as it is to the story, is handled

briskly. There’s very little description of her last few months. The parents

resolutely do not want to open the door to any theorizing. She got sick.

We tried to help. She died.

In some ways, the whole situation reminded me of a lost, American Thomas Mann story. Art can kill. It's a fatal disease, a kind of Dr. Faustus bargain with the devil, a virus that destroys. Or: is it art that's responsible, or a blind devotion to art above all else that can be as destructive as greed or sexual fixation? What is art worth? How much should you be willing to devote to creating great work? We routinely say whatever it takes, and then most people are too lazy to follow up with that commitment. But what is it worth to get into the permanent collection of the Whitney? To be an art star -- that is, to be collected by the fashionable and the rich? Is that the measure?

Let's say, we're all Zen and it's all about the work. So, are the pleasures and pains of creating something in the studio and the discipline and time spent in that worth, say, a daughter? A son? We generally see art as a positive good, or even in our secular times, as the ultimate good. But what does it cost?

Assuming that depression led to the suicide -- and, let's be clear, suicide and depression don't have to go together -- but assuming that her depression was the cause: would she have been diagnosed earlier? If you examine the work by Francesca, does it seem moody and alienated in a modern way, a romantic kind of fascination with the dark? Or can/should you reduce them to being symptomatic?

Can the exquisite kill? I'm not implying that the Woodmans themselves exhibit the kind of hysterical refinement you see in The Pillowbooks of Sei Shoganon. But what would be the consequences of pursing a purely aesthetic existence above all else? Is there a point when it crosses over from enriching daily life to becoming a weight, a heavily enforced obligation to make each moment a kind of epiphany of beauty?

The levels of pain that George, at least, must have endured, can only evoke sympathy. But somehow, you can't help but judge, weigh, and wonder.

In some ways, the whole situation reminded me of a lost, American Thomas Mann story. Art can kill. It's a fatal disease, a kind of Dr. Faustus bargain with the devil, a virus that destroys. Or: is it art that's responsible, or a blind devotion to art above all else that can be as destructive as greed or sexual fixation? What is art worth? How much should you be willing to devote to creating great work? We routinely say whatever it takes, and then most people are too lazy to follow up with that commitment. But what is it worth to get into the permanent collection of the Whitney? To be an art star -- that is, to be collected by the fashionable and the rich? Is that the measure?

Let's say, we're all Zen and it's all about the work. So, are the pleasures and pains of creating something in the studio and the discipline and time spent in that worth, say, a daughter? A son? We generally see art as a positive good, or even in our secular times, as the ultimate good. But what does it cost?

Assuming that depression led to the suicide -- and, let's be clear, suicide and depression don't have to go together -- but assuming that her depression was the cause: would she have been diagnosed earlier? If you examine the work by Francesca, does it seem moody and alienated in a modern way, a romantic kind of fascination with the dark? Or can/should you reduce them to being symptomatic?

Can the exquisite kill? I'm not implying that the Woodmans themselves exhibit the kind of hysterical refinement you see in The Pillowbooks of Sei Shoganon. But what would be the consequences of pursing a purely aesthetic existence above all else? Is there a point when it crosses over from enriching daily life to becoming a weight, a heavily enforced obligation to make each moment a kind of epiphany of beauty?

The levels of pain that George, at least, must have endured, can only evoke sympathy. But somehow, you can't help but judge, weigh, and wonder.

In the end, it terrified me. Deaths of children do that to me. I felt both sorrow and pity, and, I have to say that a few times I found myself thinking that they, the survivors, were monstrous mediocrities – but how much they had

worked to make it there, how truly brilliant and accomplished they are. And

yet, they’re only going to be Salieris to Francesca’s Mozart. And they know it.

Blog post

Filmmaker web site

IMDB

PBS/ITVS web site

03 August 2012

Betty Boop & Cab Calloway in Snow White

"This 1933 cartoon featuring Cab Calloway is remarkable for having been animated by a single individual, Roland C. Crandall, and is considered one of the best cartoons ever made. Crandall received the opportunity to make Snow White on his own as a reward for his several years of devotion to the Fleischer studio, and the resulting film is considered both his masterwork and an important milestone of The Golden Age of American animation. "

02 August 2012

01 August 2012

Patti Smith sings Banga on Letterman

Patti Smith sings about the greatest dog in all of literature: Banga, Pontius Pilate's hound in the masterpiece, The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov. And the song rocks. Proving, once again, she's one of the greatest performers alive. That she's around makes life better.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)